The Harbour of Love – Irina Wahlström and Patrik Hellman’s lives are intertwined with the Baltic Sea

Kirjainen harbour. A ferry sits motionless at the tip of the headland as a flock of seagulls flies over on their way to a meeting. Dark clouds have gathered in the sky as if painted in watercolours. The temperature hovers around 15 °C.

Text: Johannes Roviomaa

Photos: Touko Hujanen

Kirjainen (Kirjais in Swedish) is both an island and a village of the same name in Pargas, south of the main islands of Nauvo.

You can imagine this place packed with cars and boats at the height of summer. But now, in the second week of August, the harbour is quiet. Irina Wahlström, 53, and Patrik Hellman, 59, pick us up from the harbour.

The couple first met at the Port of Turku’s passenger terminal back in the 1990s, when they were both working as check-in clerks for Silja Line. The Baltic Sea has brought them together and provided them with both livelihoods and leisure activities.

We put on our life jackets and board their boat, Vattenkatten (The Sea Cat), which serves as a ferry between the mainland and the island.

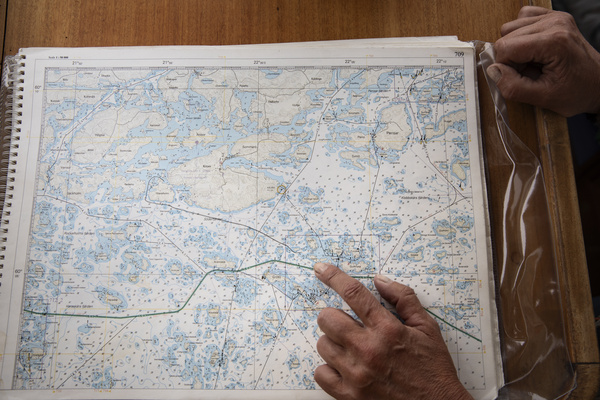

This sturdy, aluminium-hulled boat was built in 1989 at a factory that manufactures boats for the authorities. The cockpit is equipped with a VHF radio, a depth gauge, radar, and a chart plotter for tracking the boat’s position.

“I was born by the sea and took my first ever steps in a boat,” says Irina Wahlström.

The couple also spends their summers sailing in the Åland Islands and surrounding area and particularly enjoy touring natural harbours.

The Baltic Sea is shallow, with an average depth of 55 metres and a deepest point of 460 metres. And it’s even shallower where we are now: the depth gauge indicates that we have 5.5 metres of water beneath our feet.

We proceed through the largest private conservation area in the Archipelago Sea at a leisurely pace.

The Gullkrona conservation area covers 4,800 hectares, which is about a fifth of the area of Helsinki. Or more than 6,700 football fields. And just like in a game of football, we should respect the rules when it comes to marine conservation.

These waters have been protected since last autumn, and the conservation area covers both open sea and small islets. Aquaculture, the extraction of sea sand and other intensive modifications of the seabed are prohibited within the conservation area. Anchoring is prohibited in areas where endangered eelgrass meadows grow, and movement is also restricted in the vicinity of bird islets during the nesting season.

We sail along the western side of the marine conservation area and pass its centre, Gullkrona Island.

Red cabins sit side by side on the cliffs, embraced by conifers. Near the shore, cormorants loiter on the rocks ready to receive guests.

Until a few years ago, Gullkrona Island was inhabited all year round.

“The Erikssons always went out fishing with their nets around four o’clock in the morning,” says Wahlström, reminiscing about former residents. And they didn’t go fishing for nothing: she says that, back in the 1970s, you could catch as much cod, pike, and flounder as you wanted in the Baltic Sea. These catches used to provide a good livelihood for fishing families.

But times have changed. Industrial fishing, and rainbow trout farms in particular, have since stolen the livelihoods of traditional fisherfolk.

The Gullkrona marine conservation area was originally established on the initiative of BSAG’s Saara Kankaanrinta and Ilkka Herlin. They are both BSAG’s founders and the current owners of Gullkrona Harbour. Wahlström says that Herlin and Kankaanrinta fell in love with the island and also got married there.

Wahlström and Hellman were involved in establishing the Gullkrona marine conservation area with about twenty members of the fishing community and representatives of Finland’s environmental administration.

Their cottage is also located there.

Wahlström says that, from a landowner’s perspective, conservation only required “a few online meetings organised from Keilaranta.”

Wahlström opens the throttle. We approach their cottage at a speed of about twenty knots, that is, around forty kilometres per hour. It feels faster on the water than on land.

On the way, we pass Bultarna Island, which is part of the state-owned Archipelago National Park.

Hellman says that, in spite of the rules in force in national parks, you still get daytrippers or boaters irresponsibly lighting open fires on the island. One year, the weather in the archipelago had been very dry and there was a bracing northerly wind. An emergency vessel was called to the island to deal with a fire, and arrived in fifteen minutes with sirens blaring to extinguish a large campfire.

Other aspects of archipelago etiquette are also sadly lacking at times.

“Not all boaters understand the rules and simply sail around however they please. And usually, the bigger and faster the boat, the less respect they show for other seafarers,” says Hellman.

Hellman disapproves of boaters who enter and exit harbours at full throttle, causing a lot of swell that can damage vessels moored in the harbour. There are currently no fellow boaters to be seen – at least, not by human eyes. The cormorants flying above us may be able to spot some other seafarers.

A love for the Baltic Sea runs through the Wahlström family. Irina’s father, Antti Wahlström, used to sail the world’s oceans competitively and was involved with World Sailing (formerly the International Sailing Federation).

”Life in the archipelago is a lifeline for us. Out here things are more simple: you have to fetch water and empty the slop bucket yourself.”

In the archipelago, the couple is also able to de-stress and leave all the hustle and bustle behind. Their cottage has a gas-powered stove and a fridge, but no electricity or running water.

“You can live however you please on this island – swim naked without a care in the world. You can be yourself,” says Wahlström.

“We live at the mercy of nature. The Archipelago Sea is our television. And nature can be quite cruel sometimes,” says Hellman.

The couple has a sense of humour, and it shows. They’ve named all of the creatures that live near the island in imaginative ways. The viper that lives on the island is named after the Russian-born composer Igor Stravinsky.

The islet is also home to a seagull called Néro. His wife is Lady Gaga, because “seagulls make a ga-ga-ga noise when they want to sound threatening,” says Hellman, demonstrating.

However, the island’s most important inhabitant is an oystercatcher that has been nesting there since 1998. This black-and-white bird with its orange beak has been christened Jack, aka the Red Baron. The oystercatcher has also been immortalised on a flag designed by Wahlström’s father, which now flies over the island’s jetty. The island has been visited by sailors from near and far – from Denmark, the Netherlands, and England.

Patrik and Irina feed Jack the Oystercatcher with dry cat food, and Jack wakes the couple up every morning by tapping on the boat’s window with his beak. The couple sleep on the boat. This year, the oystercatcher has had three chicks that have already headed south – to the Netherlands, England, or somewhere in Africa.

We finally arrive on the island. The summer cottage season starts in mid-May and ends in September. Whenever the weather allows, they set out from their home in Pargas right after work to spend the weekend at the cottage.

Hellman moors the boat on the dock, which has space for two vessels. The couple have about three of the island’s eleven hectares at their disposal. “There’s been some flooding due to the exceptionally high water level. The island looks completely different than normal,” says Wahlström.

Wahlström’s grandfather was the photographer Osvald “Hede” Hedenström (1913–1998). He was one of Finland’s first press photographers.

It was Hedenström who bought the cottage in 1964 after eventually persuading the Erikssons – a fishing family who lived on Gullkrona Island – to sell.

The white-tailed eagle circling above the island has had two chicks this year.

Inside the guest cabin, which was added in 2002, there’s a bronze sculpture of Irina’s uncle, Kaius Hedenström (1943–2006), who was also a photographer. He once helped to save the white-tailed eagle from extinction by, for example, participating in their winter feeding at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s.

With a wingspan of up to 2.5 metres, the white-tailed eagle is Finland’s largest bird. It starts nesting in April. In the early 1900s, the Finnish state was still paying a “pest removal” bounty to anyone who shot a white-tailed eagle.

However, long-term conservation work managed to save the white-tailed eagle from extinction. Experts estimate that there are now more than a thousand white-tailed eagles.

We start by checking out the island on foot. The beach used to be sandy. We pass a water lily pond that the couple wants to revive. It has suffered from eutrophication – just like the Baltic Sea.

“An alder dropped all of its leaves into the pond, and it’s not good for the water when biomass volumes grow too large,” says Hellman.

The state of the Baltic Sea has improved over the past few years. This is evidenced by an increase in kelp. A new buoy was installed on the shore near the couple’s cottage last year, and a diver said that “the water is as clear as in an aquarium”.

Strong winds uprooted some archipelago pines during the summer. The couple often like to sit on the south side of the island in wooden deckchairs, scoring passing sailors’ progress like sailing judges, but they weren’t able to this year due to strong gusts of wind. Terns and seagulls nest on the west side of the island, so the couple have no business going there.

Maritime sunburst lichen grows on the rocks, and it looks as if someone has been painting peace signs on the rocks with brushes.

It starts raining a little and the wind picks up. Time to go inside. The smell of tar hits your nostrils as you enter the cottage.

Wahlström speaks a mixture of Swedish, Finnish, and English as she lays the table with coffee and buns. We can see wagtails, swallows, and common gulls through the window. Most of the birds that live in the archipelago have already set out on their autumn migrations.

Hellman lights a fire in the stove and parks himself on a chair.

Hellman is the CEO of Kaskinen Harbour. He has a long career in maritime transport and gambling games behind him.

Both of their relatives have also made a living in managerial positions at shipping companies. Patrik Hellman’s godfather was once the CEO of Silja Line and Irina Wahlström’s godfather was the CEO of Finnlines.

The couple doesn’t have any children together, but Hellman has a son from a previous marriage. He is studying to be a sea captain.

About 1.2 million tons of cargo pass through Kaskinen Harbour each year – about one percent of Finland’s industrial vessel traffic.

“The same rules and procedures should apply to ship waste collection in all harbours,” says Hellman.

Ships leaving Kaskinen Harbour sail not only to the Baltic Sea region but also to England, the Netherlands, Belgium, North Africa, and Italy. In the future, they will also cross the ocean to the United States.

Wahlström works as a project manager for shipping-related projects in the Laboratory of Industrial Management at Åbo Akademi University. She is a qualified biochemist and has also studied for an MBA in Shipping at Greenwich University in London.

She is currently investigating how maritime logistics could be made more efficient and ships more environmentally friendly. THE SEA is one of Åbo Akademi’s spearhead projects and involves collaboration between researchers in the fields of marine biology, industrial management, public administration, and maritime law.

Wahlström says that vessel traffic is regulated at three levels: the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the EU and national regulations rule the waves.

“Shipping has typically lagged where environmental issues are concerned. Ships have long lifespans. The regulations haven’t been dynamic enough,” says Wahlström, somewhat diplomatically.

Stricter environmental regulation is required for marine conservation. Globally, merchant shipping generates about three percent of all emissions.

Boaters’ wastewater is another environmental issue. Wahlström wonders how many people make use of the floating pumping stations found at harbours, which can be used to empty boat waste tanks free of charge. Harbour fees usually include toilets and showers in addition to other services.

“We have a 40-litre tank, for example. That’s not much. Marinas should have some kind of system that takes verified use of pumping stations into account in their harbour fees,” says Wahlström.

If you love something, you also want to protect it.

In the Protectors of the Baltic Sea -article series, we dive beneath the surface, visit the largest marine conservation area in the Archipelago Sea, take a ride on a farmer’s tractor, travel on a cargo ship, and talk to an artist and an entrepreneur.

Johannes Roviomaa (b. 1991) is a journalist, screenwriter, and visiting researcher at the Arctic Centre. He specialises in climate change, the Arctic region, and the food system. Along with his team, Roviomaa has received both the State Prize for Popularization of Science (2018) and the Kanava Award (2017).

Touko Hujanen is a photojournalist who specialises in reportage. He has received several awards, such as Photojournalist of the Year (2019, 2018), Press Photographer of the Year (2011), and the Discovery Award (2020).